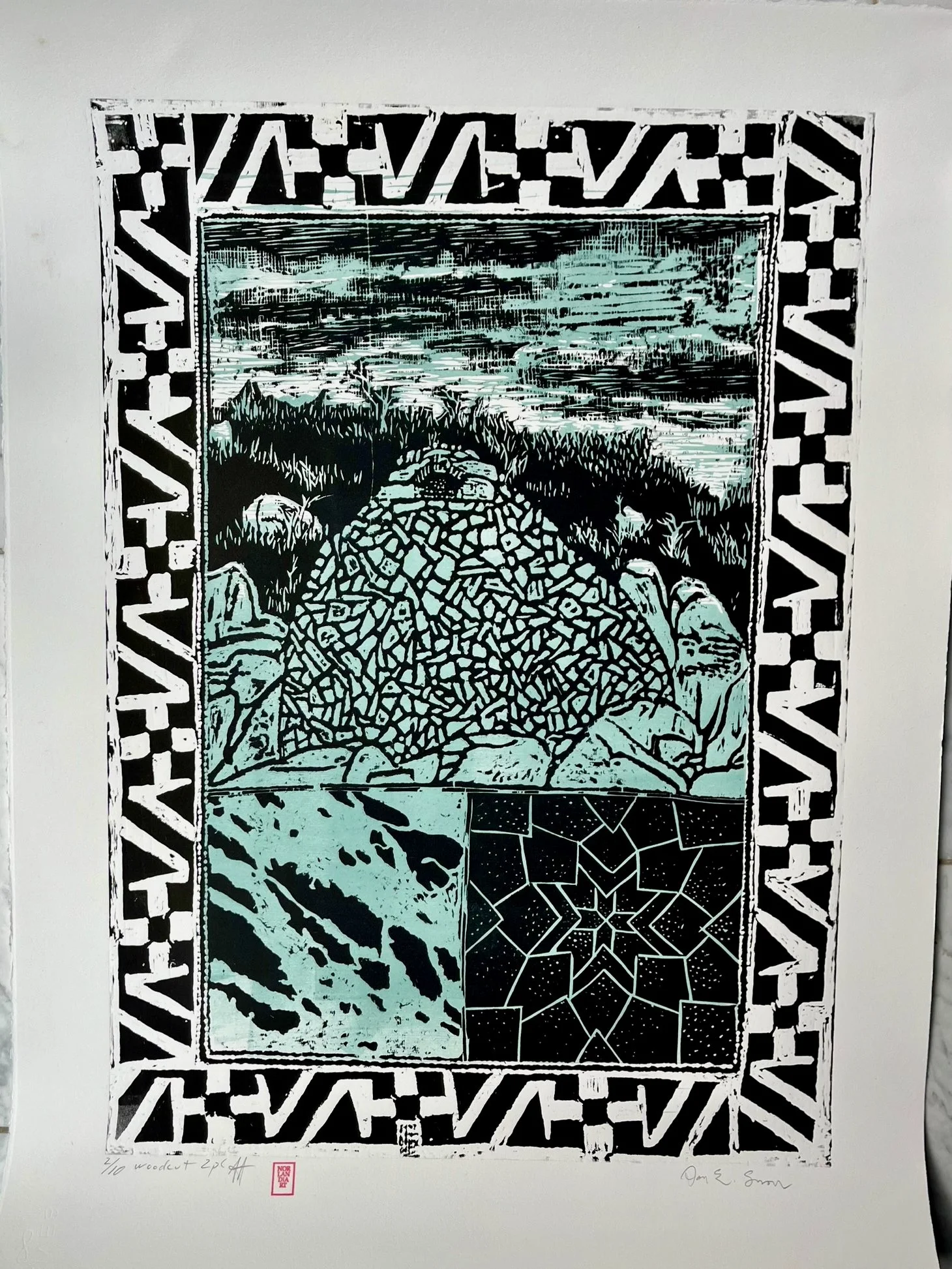

The imagery I drew on for the woodcut depicted the recently built sculpture, a slate floor that I designed and laid for our host, and a bird's eye view of the surrounding islands. Bordering the three scenes was a pattern adapted from a rug in the cottage where we stayed. The print extended my relationship to the land art beyond the time I spent making it. And it was a purely personal artwork produced in a manner that harkened back to my earliest artistic strivings. Sometimes the best direction forward is discovered by going back.

Read MoreIt started for me with the rejuvenation of those original turnpike walls. By the second year on the property I was designing and building a circular sunken garden space next to the house under construction. One wall section reached 11’ in height. During the third trip around the sun the site saw more dry stone walls rise around a greenhouse and attendant herb and vegetable gardens.

Read MoreA cyclorama (sike) for Mission Farm was conceived as a companion piece to the Odeon constructed in 2023. The seating space of walls and terraces on the hillside called out for a response from the presentation area. If the Odeon was a half-shell, a sike would complete the circle. A sike so close to the north side of the stone church would need to assert itself but not be overbearing. It would need to have textural compatibility with the Odeon but not simply be an enlargement of its footprint.

Read MoreMaybe it comes from experience, or maybe it is innate, but I do have a nose for stone. Time and again I stumble upon obscure sources of loose stone if I just start wandering around. The talent, if it can be called that, extends to moments during the walling day when a particularly sized and shaped stone is required for a spot on the wall. Without it being in sight, I will ferret into a stock pile to immediately come up with the hidden gem, waiting just below the surface.

Read MoreBefore 2023 gets too distant in the rear-view mirror, now’s a good time to catch a reflection of the year’s activities. I was joined on the 2023 constructions by a number of wonderful client partners, collaborators and dry stone professionals. All gave it their all, and I can’t thank them enough.

Read MoreReaders may well wonder “What’d it take?” when viewing images of the sunken garden space and surrounding hardscape I built last fall in Marlboro, Vermont. It was work done with skill, efficiency and pride, by me and a handful of compatriots. As with other stone endeavors, it required the marshaling of materials, equipment and craft.

Read MoreOver the years, experience taught me that not all my ideas work, but that the most risky ones, when they did, turned out to be the most rewarding. If I wanted the Odeon to be something special, I had to have faith. Architectural details from the church have informed the Odeon’s design. A seating arrangement of granite slabs, their surfaces speckled with iridescent mica like the church’s facade, are set atop retaining walls built in a matrix style that emulates that of faceted, stained-glass windows.

Read MoreThe 2023 maple season is off with a bang. Three boils in the sugarhouse have yielded several gallons of heavenly sweetness. Frosty nights and sunny days get the sap running. Our 260 buckets will be full again before we know it. Stop by the sugarhouse if you see see steam pouring from the cupola. There’s a taste of Vermont essence waiting for you.

“Sugaring off” begins our yearly activities. To see what fun we had last year take a gander at the 2022 newsletter.

Read MoreThe Stone Trust leads a tour of notable stone walls and other dry stone structures as part of BMAC’s “Hidden in the Hills” series. The tour will begin and end at The Stone Trust, located at Scott Farm in Dummerston, Vermont. Participants will begin with a short walking tour at The Stone Trust, followed by a guided tour of nearby stone structures. Amy-Louise Pfeffer, Executive Director of The Stone Trust, and I will host the event. Come and enjoy.

Read MoreThe recent 2-Day Cheek Rebuild workshop that I instructed saw four enthusiastic participants complete their own free-standing cheekend, achieving personal satisfaction from work well done, and a certificate from The Stone Trust, to boot! Congrats to Darrin, Lou, David and Jonny for rising to the challenge.

Read MoreCraft skills typically used for making something new are also practiced to repair something old. Many a waller has cut their teeth in the trade by rebuilding broken gaps in old fence lines. Mending a section of dilapidated, dry stone wall is a form of stitchery, too. When done with respect for what's been accomplished by others in the past, repairs can feel like a partnership that's taken place over centuries.

Read MoreHours and days of grinding labor culminate in a finished structure but somehow it’s the intermissions in the process that are remembered, the many cracks of light that shine through the monolith of physical exertion that is dry stone walling.

Read MoreEvery project has the treasure of time locked inside. The key to spending it wisely is to embrace the unknowns. Seek out and dwell on every moment’s mystery and the day’s toil will pass in a flash.

Read MoreI was invited to talk to the assembled guests about the built landscape. We led the group through the lush gardens, pausing to tell stories and answer questions. Any puzzlement on the faces of the visitors was completely understandable. Half of what we described was fiction; a historical ruse amplified by the very real existence of the dry stone curiosities I constructed there.

Read MoreBy expanding my repertoire to include other skilled practitioners of the craft I can now see how there’s nothing lost and much to be gained. The satisfaction of successfully completing a piece is shared by all, without any one having to do it all.

Read MoreBuilding with dry stone is the act of moving bits of rock from one spot to another. Not much new, physically, happens to the material, but the builder’s psychic space gets charged with fresh energy all day long. Its intensity and positivity define the total experience.

Read MoreSince I’ve only been on the receiving end of interview questions I don’t know how they’re properly crafted but I can tell when they have been. A good interviewer opens a door and asks the subject to step into their own world. I was pleased to be asked by Tom Christopher to be interviewed for his podcast Growing Greener.

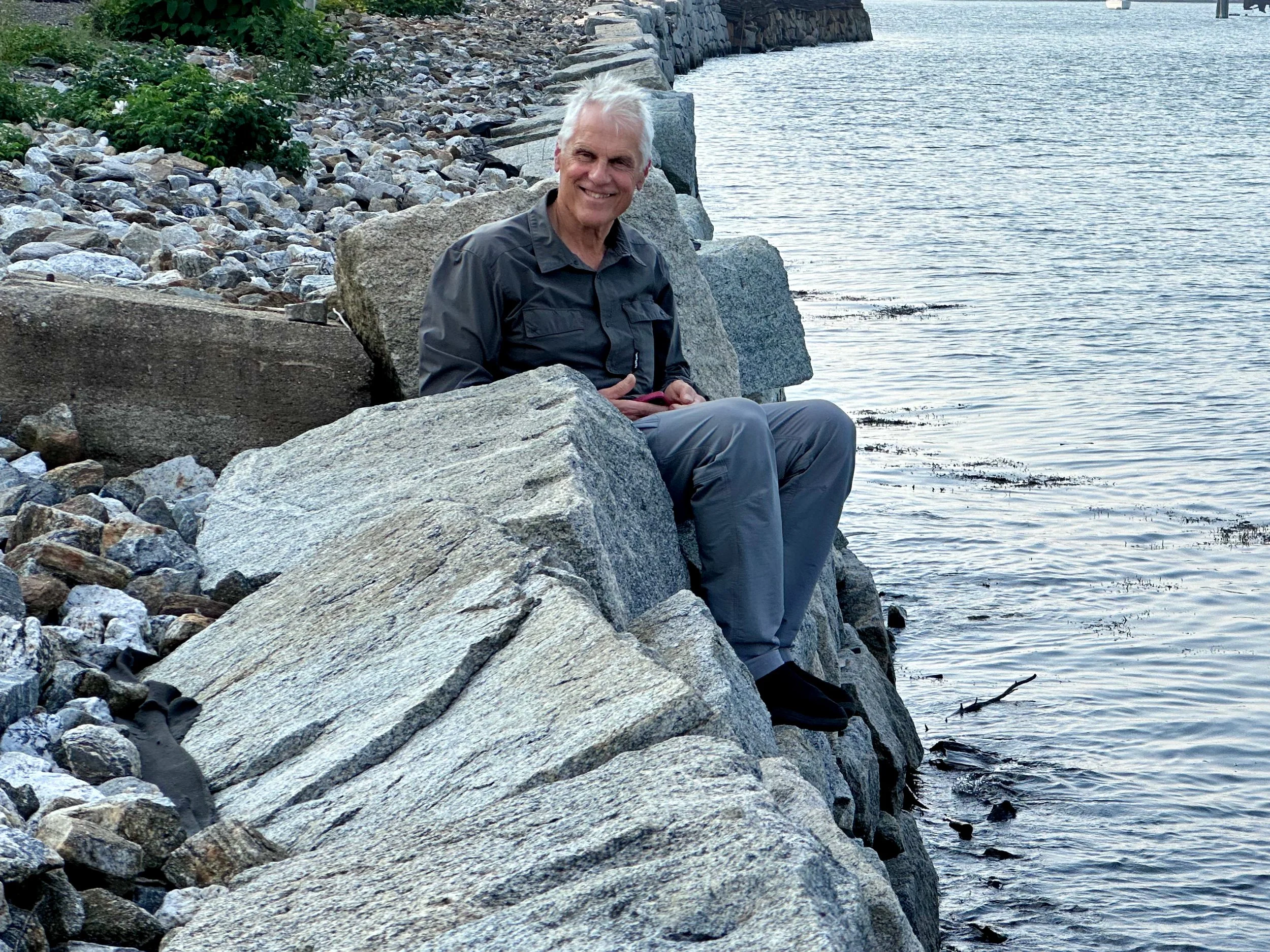

Generations of Vermont farmers have picked stones from their fields, to, in Robert Frost’s words, “subdue the growth of earth to grass.” In the 20th century, the diesel-powered bulldozer unearthed and shoved boulders up into huge, mid-field heaps. Three such mounds provided the stone for the walls I recently completed around the Big Red Barn in Winhall Hollow.

Read More